Black & Indigenous Research Guide

Explore records of Black and Indigenous people in early New England Congregational churches.

This Research Guide was created in 2021 by Dr. Richard J. Boles, Department of History, Oklahoma State University and Jules Thompson, then CLA Archivist. It is periodically updated by CLA staff.

New England’s Hidden Histories is pleased to highlight a number of records relating to Black and Indigenous people in early New England Congregational churches. Though historians have long recognized that the early Congregationalists’ missionary impulse led them to establish Native American “praying towns,” and that some Congregational churches included Black, Indigenous, and mixed-race parishioners, including people enslaved by white parishioners and clergy, the experiences of these underrepresented populations have received relatively scant scholarly attention. In fact, the participation of Black and Indigenous people in early American Congregational churches was both significant and longstanding, as were their contributions to Congregationalism as church members, lay preachers, and ordained ministers.

New England’s Hidden Histories, whose larger mission is to digitize, transcribe, and make accessible online New England’s earliest Congregational manuscript church records, is the first and only scholarly project to gather systematically and make available online records pertaining to the the experiences of Black, Indigenous, and other peoples of color in these early Congregational churches. Highlights of our growing collection include records from Black churches, including those of the Abyssinian Church of Portland, Maine, manuscript records from Natick, MA, the only documents known to survive from a church that was simultaneously Indigenous and English Congregationalist, the only known relation of faith written in the hand of an enslaved person, and many other exceptionally scarce and valuable documents. NEHH has transcribed many of these manuscripts. For information on and contextualization of the specific documents in our collections, please see the multi-part research guide below.

Interracial and Separate Churches

During the colonial era, Black and Indigenous people participated in numerous predominantly-white Congregational churches through baptism, communion, public worship, singing, catechism classes, and other shared religious activities. Their participation was usually in the context of colonization and enslavement or bonded servitude, but some Black and Indigenous peoples had spiritual as well as practical reasons (such as access to education) for affiliating with these churches.1

During the widespread religious revivals of the early 1740s, some Narragansett, Pequot, Mohegan, Niantic, Wampanoag, and other Indigenous peoples attended and participated in majority-white Congregational churches. Additionally, many Black people, enslaved and free, affiliated with both evangelical-leaning and more traditional Congregational churches throughout the eighteenth century. The manuscript church records digitized by New England’s Hidden Histories are essential for understanding the religious affiliations of Black and Indigenous peoples because published vital records and nineteenth-century church directories commonly omitted information about eighteenth-century Black and Indigenous church members.2

Partly because they faced prejudice from white Christians, including segregated seating and proscriptions against voting and holding leadership positions, Black and Indigenous people in New England increasingly began to form their own Congregational churches. For example, dozens of Narragansett men and women in the early 1740s joined Joseph Park’s Congregational church in Westerly, Rhode Island, but about 1749, most of them left this church and founded their own congregation under the leadership of Samuel Niles (Narragansett). Black people slowly gained freedom from slavery in New England after the 1780s, and in the early nineteenth century, they founded Congregational churches in Newport, RI, Portland, ME, and New Haven, CT.3

Documenting Slavery and Abolitionism

Early records related to Congregational churches, organizations, and individuals are rich sources for studying not only the religious lives of Black and Indigenous peoples but also for social, political, gender, and economic histories. Along with probate records, court documents, personal papers, and occasional censuses, the records listed here provide important sources for understanding abolitionist movements and the prevalence and experiences of enslavement in New England.4

In 1754, an enslaved man named Greenwich, who attended the Separate Congregational Church in Canterbury, CT, made an early public statement against slavery in New England. During the era of the American Revolution, other Black people used religious ideas likely gained from participation in Congregational churches to call for the abolition of slavery, including Rev. Lemuel Haynes (1753-1833) before he was ordained as the first Black Congregational minister.5

Some white Congregationalists, including Rev. Samuel Hopkins (1721-1803), eventually joined these Black Christians in calling for emancipation and an end to the international slave trade. The records in these collections help explain how legal slavery gradually ended in New England. After a several decade hiatus, some white Congregational churches and Christians rejoined northern Black people to fight against the expansion of slavery into western territories and to fight for the abolition of southern slavery. The Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, formed in 1834 and whose records have been digitized, is an example of this trend.6

Indigenous Congregationalists

Congregational churches were founded for and sometimes by Indigenous people in Massachusetts during the seventeenth century, and other Indigenous-led churches flourished starting in the 1750s in southern New England. Puritan minister John Eliot (c. 1604-1690) helped to establish “Praying Towns” for Christian Indigenous peoples in Massachusetts, and Thomas Mayhew Jr., Peter Folger, and Richard Bourne helped establish churches among the Wampanoag on Martha’s Vineyard and Cape Cod.7

Dozens of Wampanoag and other Indigenous people received religious training from English colonists and became missionaries and pastors to their own peoples. They helped Eliot translate the Christian scriptures into the Eastern Algonquian Wôpanâak language (Mamusse wunneetu-panatamwe Up-Biblum God) and created a rich array of Wôpanâak language sermons and devotional materials.8

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (and sometimes continuing to the present), Wampanoag, Narragansett, Pequot, Mohegan, and Montaukett communities maintained their own Congregational, Baptist, or ecumenical congregations. Congregational churches and associations continued to sponsor Indigenous and white school teachers, missionaries, and ministers in these communities, including the Rev. Gideon Hawley in Mashpee, Massachusetts.9

Notes

1 Richard J. Boles, Dividing the Faith: The Rise of Segregated Churches in the Early American North (New York: New York University Press, 2020); John Wood Sweet, Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730–1830 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003); Richard A. Bailey, Race and Redemption in Puritan New England (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

2 Lise Breen notes that the published Gloucester Vital Record do not include several enslaved people who are clearly listed in the First Parish Church records. Other published church records and directories from the nineteenth century likewise omitted the racial labels found in the original church records. Old South (Third) Church in Boston did not racially identify its historic Black church members on lists printed in 1833, 1841, or 1883.

3 Linford D. Fisher, The Indian Great Awakening: Religion and the Shaping of Native Cultures in Early America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); Boles, Dividing the Faith.

4 Jared R. Hardesty, Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston (New York: New York University Press, 2016).

5 Erik R. Seeman, “‘Justise Must Take Plase’: Three African Americans Speak of Religion in Eighteenth-Century New England,” William and Mary Quarterly 56, no. 2, (Apr., 1999): 393-414; Christopher Cameron, To Plead Our Own Cause: African Americans in Massachusetts and the Making of the Antislavery Movement (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2014); John Saillant, Black Puritan, Black Republican: The Life and Thought of Lemuel Haynes, 1753-1833 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

6 Joseph Conforti, “Samuel Hopkins and the Revolutionary Antislavery Movement,” Rhode Island History 38, no. 2 (May 1979); Kenneth P. Minkema and Harry S. Stout, “The Edwardsean Tradition and the Antislavery Debate, 1740–1865,” Journal of American History 92, no. 1 (June 2005): 47–74.

7 Richard W. Cogley, John Eliot’s Mission to the Indians before King Philip’s War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999); David J. Silverman, Faith and Boundaries: Colonists, Christianity, and Community among the Wampanoag Indians (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

8 Edward E. Andrews, Native Apostles: Black and Indian Missionaries in the British Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013); Cogley, John Eliot’s Mission.

9 Fisher, Indian Great Awakening; Andrews, Native Apostles; Jean M. O’Brien, Dispossession by Degrees: Indian Land and Identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650–1790 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Using this Guide

This multi-part research guide is designed to facilitate the identification of early archival sources in the CLA’s collections that relate to Black and Indigenous people within the Congregational milieu. All records date from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. For the most part, these records are digitized and available to view online, but in some cases supplemental physical-only records in the CLA’s collections are also included.

Note: Materials in these records contain outdated and harmful language.

In This Guide

Firsthand Writings by BIPOC

Colonial-era and early-nineteenth-century materials written by Black and Indigenous people have rarely survived and were rarely collected in deliberate ways by libraries and institutional archives before the twentieth century. Sometimes restricted access to literacy, attempted erasures, and ambivalence to understanding their point of views were part of the systematic oppression that Black and Indigenous people faced in New England and elsewhere. These facts make the availability of these firsthand writings by Congregational clergy and laypeople all the more significant.

Note: Materials in these records contain outdated and harmful language.

Rev. Lemuel Haynes

Rev. Lemuel Haynes (1753–1833) is often described as America’s first fully ordained Black minister. Ordained in 1785, he served as pastor at several Congregational churches, including Torrington, CT, West Parish Church of Rutland, VT (now West Rutland's United Church of Christ), Manchester, VT, and the Congregational Church in South Granville, NY. An inquisitive student, soldier of the American Revolution, and early abolitionist, Haynes preached in support of equality for Black Americans across New England and New York. His preaching was well-regarded by numerous Trinitarian or Orthodox Congregational Ministers. Middlebury College granted Haynes an honorary master of arts in 1804. His sermon, Universal salvation, a very ancient doctrine, first preached in 1805, was a popular rebuttal to Universalist doctrines and was published in numerous editions. Rev. Timothy Cooley published a biography of Haynes in 1837.

Manchester, Vt. First Church Records

Much of the first manuscript record book of the First Church of Manchester, VT was written by Rev. Haynes, specifically the portions dating from 1818-1822.

Granville, Mass. Congregational Church Records

While serving in Rutland, VT Haynes wrote a series of letters to Rev. Timothy Cooley, the pastor of the above Granville church, primarily discussing ministry and local current events. One of these items is a reply to his daughter Electa updating her on family and friends at the end of her school year. Also included is Haynes's handwritten epitaph.

Bennington, Vt. First Church Records

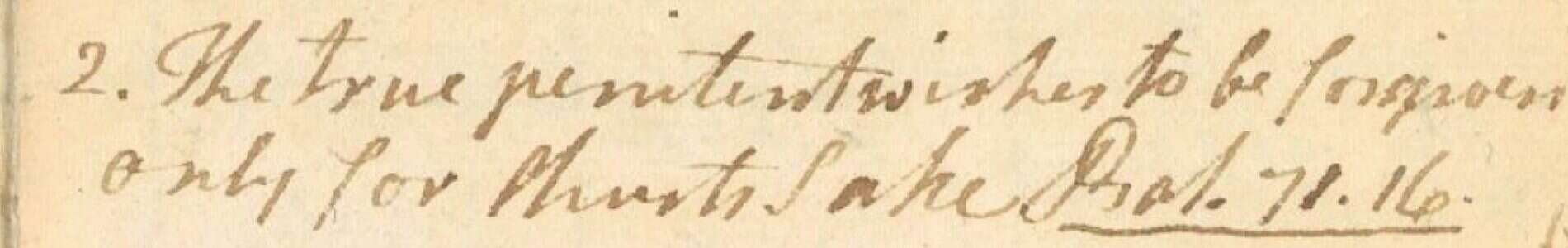

These records include items of correspondence received from Rev. Lemuel Haynes while he was minister at Manchester, VT. They include a manuscript sermon on the nature of repentance (first preached 1801), and a signed letter, dated 1806, to Rev. Elihu Smith of Castleton regarding a difficulty in the Congregational Church at West Rutland. Also included are an engraved portrait of Rev. Haynes and a short biographical sketch.

The Middleboro, MA First Church records contain a disciplinary confession from parishioner Alice Anthony (d. 1790). Also referred to as Else, she is identified in other documents as an Indigenous woman from the local Namasket/Pokanoket band of the Wampanoag people. She was admitted as a member of the First Church of Middleboro on January 24, 1742 and produced her confession many years later, on June 6, 1783. Though the document was probably written with the assistance of the local minister, it is the only document of its kind known to exist. In the confession Anthony apologizes for "the scandalous sin of intemperance" and for staying away from public worship, and asks the congregation to receive her back into the church and to pray for her.

Catharine Brown was born sometime around 1800 to John and Sarah Webber Brown. Her family was part of the Creek-Path Cherokee community. Having already begun to learn English, Catharine joined the Brainerd School in 1817. In 1820, she began teaching at the Creek Path Mission but soon returned home to care for her parents following the death of her brother, John. She remained with her family and soon started to also get sick. She died on July 18th, 1823. The Catharine Brown papers contain ten letters written by Catharine, a copy of her diary, and 14 notes and letters from various people discussing Catharine and her legacy. The 25 items in the collection are available in PDF format.

Phillis or Philesh Cogswell was, like Flora/Flory (see entry below), a member of the evangelical Fourth Church of Ipswich (The "new" Chebacco church). She was enslaved in the household of Jonathan Cogswell. Phillis/Philesh initially began attending church during the revivals of the 1740s, but she had never become a full member and felt her piety decline over the years. Her decision not to join a church changed with the onset of the Seacoast Revivals of the 1760s. On April 22, 1764 she submitted a formalized relation of faith to the congregation as part of the process of seeking full membership. While large parts of the document adhere to standard phrasing, there are also individual biographical details from her life. Other records relating to Phillis/Philesh include her personal signature, suggesting an ability to write, which was extremely unusual for an enslaved person and for women in general at the time. Following her application, she was baptized into the Fourth Church of Ipswich as a full member in May or June of 1764. Other contemporary records relate that Cogswell had been manumitted from slavery by 1785. For further information please see Erik R. Seeman's article "'Justise Must Take Plase': Three African Americans Speak of Religion in Eighteenth-Century New England."

The Fourth Church in Ipswich, also known as the "new" Chebacco church or the Separatist Church, was formed by "New Light" revivalists during the First Great Awakening of the 1730s-40s. The evangelical church counted four enslaved persons among its first twenty-two full members. One of these was a woman named Flora or Flory, enslaved by Thomas Choate of Ipswich. On July 23, 1749 she addressed a formalized confession of sins to the congregation. In the written record of the confession, she requests forgiveness for largely undefined transgressions, and expresses regret that her flaws could have negatively impacted the revival movement. Specific phrasings within the document suggest that she may have engaged in lay preaching during the midcentury religious revivals. For further information please see Erik R. Seeman's article "'Justise Must Take Plase': Three African Americans Speak of Religion in Eighteenth-Century New England."

The Middleboro, MA records include a relation of faith submitted by Anna Wright, Cuffee/Cuffy Wright's wife, racially identified in other records as Black. This formal document records Anna's spiritual biography in accordance with Congregational conventions of the time. She produced the relation when seeking full membership to the Middleboro First Church in 1796, 23 years after her husband had been admitted.

Cuffee/Cuffy Wright was enslaved by Rev. Sylvanus Conant, minister of the Congregational Church in Middleboro, MA, and is referred to elsewhere as "Cuffy the African." He sought membership in the same church by submitting a formal relation of faith document in 1773 in which he detailed his spiritual journey. Cuffee/Cuffy's relation is the only such document discovered thus far that was written in the enslaved person’s own hand. The grammar, spelling, and syntax of the document vary at times, but thematically it adheres to the Calvinist theology and praxis of eighteenth-century Congregationalism. For further information, please see James F. Cooper's article "Cuffee’s ‘Relation’: A Faithful Slave Speaks Through the Project for the Preservation of Congregational Church Records."

BIPOC Churches and Institutions

Only six Black Congregational churches were established in New England prior to the Civil War: the Dixwell Avenue Church in New Haven, CT, the Talcott Street Church in Hartford, CT, the African Union Congregational Church in Newport, RI, the Abyssinian Church in Portland, ME, the Second Church of Pittsfield, MA, and the Black church in Springfield, MA. New England’s Hidden Histories is pleased to make available online, in cooperation with the Maine Historical Society, the records of the Abyssinian Church of Portland, which have been both digitized and transcribed.

Indigenous peoples in New England maintained their own churches in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, sometimes in cooperation with a white missionary and sometimes independent of white influence or oversight. Some of the seventeenth-century congregants were known as “praying Indians” and the towns in which they came to reside were referred to as “praying towns.” During the eighteenth century, predominantly Indigenous churches existed on Martha’s Vineyard, near Sandwich or Bourne, MA; at Mashpee, MA; Stockbridge, MA; Mohegan, CT; Farmington, CT; near Charlestown, RI; and at Montauk, Long Island, but few written records from these congregations are extant. Writings of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Indigenous ministers are slightly more prevalent. A single page of a marriage register for the years 1749-1771 has survived, written by the Gay Head congregation’s minister Zachary Hossueit (Wampanoag).1 The writings of Samson Occom (Mohegan), Joseph Johnson (Mohegan), William Apess (Pequot), records of missionary organizations, and the journals of Gideon Hawley are valuable sources of information about these Indigenous churches.2

Note: Materials in these records contain outdated and harmful language.

Natick was the location of the first of fourteen Indigenous praying towns, and both white and Indigenous ministers led this congregation between 1660 and 1719. A new Congregational church was organized in Natick in 1729 by the white minister Oliver Peabody, who was employed by the New England Company missionary society. The First Church in Natick was, before approximately 1800, simultaneously an Indigenous and English congregation. There were also a sizeable minority of congregants who were identified as Black in the earliest church registers, as well as increasing numbers of white members. Natick Indigenous people faced numerous challenges, including the deadly forced removals to Deer Island in 1675 during King Philip’s War and the loss of political control of the town, but the Indigenous presence in this town and church persisted in the eighteenth century. The first volume of records includes a list of “those Indians that have Dyed from among us,” which can be used as an index to track the activities of Indigenous people in the church, many of whom had anglicized names.3

Portland, Maine. Abyssinian Church

The Abyssinian Church in Portland, ME was formed after Black parishioners of the Second Congregational Church in Portland petitioned the state Legislature for their own church in 1828. They had suffered discrimination at the hands of the majority-white congregation. The newly formed church was an important center for the abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad. The church and society record books of the Abyssinian are currently the only records of a pre-Civil War Black Congregational church available online, and may be the only online digitized records of an antebellum Black church of any denomination.4

Notes

1 Ives Goddard and Kathleen Joan Bragdon, Native Writings in Massachusett, two volumes (American Philosophical Society, 1988), 1:66-73.

2 Samson Occom, The Collected Writings of Samson Occom, Mohegan, edited by Joanna Brooks (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006); Joseph Johnson, To Do Good to My Indian Brethren: The Writings of Joseph Johnson, 1751-1776, ed. Laura J. Murray (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998); William Apess, On Our Own Ground: The Complete Writings of William Apess, a Pequot, ed. Barry O’Connell (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992); Edward E. Andrews, Native Apostles: Black and Indian Missionaries in the British Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013).

3 Jean M. O’Brien, Dispossession by Degrees: Indian Land and Identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650–1790 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

4 H.H. Price and Gerald E. Talbot, Maine’s Visible Black History: The First Chronicle of Its People (Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House Publishers, 2006), 143-8.

Indigenous-Focused Records

The collections below have been divided into two categories: personal papers and manuscripts relating to Indigenous peoples, and materials written in Indigenous languages.

Note: Materials in these records contain outdated and harmful language.

Hawley, Gideon. Missionary Journals

Minister and missionary Gideon Hawley worked for the Society for Propagating the Gospel among the Indians under the supervision of Jonathan Edwards. In 1754, Rev. Hawley accepted a position from the Society to establish a mission among the Six Nations (Haudenosaunee) on the Susquehanna, near the contemporary town of Windsor, New York. With the arrival of the Seven Years’ War, Hawley returned to Boston and accepted a commission as chaplain to Colonel Richard Gridley's regiment. In 1758, he was selected as minister by a community of approximately 300 Mashpee living in Mashpee, Massachusetts. These digital collections consist of four consecutive journal volumes spanning 1754-1806, covering Rev. Hawley's travels through Mohawk country, the Six Nations, and his ministry in Mashpee. In addition to correspondence and journals, the records include a table of "Indian statistics" and a 1756 map of Onohoguage villages in New York. These diaries contain a significant amount of material about the conditions at Mashpee and some individuals in that community.

References to the Wampanoags of Martha's Vineyard are frequent in the Diary of the Rev. William Homes, a teacher and minister in Chillmark, MA. Rev. Homes' own church, the Congregational Church in Chillmark, was located approximately two miles from a separate Wampanoag church of Chillmark. In the absence of records from the Wampanoag church, Rev. Homes' diary provides some insights into its history.

Mamusse wunneetu-panatamwe Up-Biblum God

Also known as the "Eliot Indian Bible," this Wôpanâak-language translation of the Geneva bible was created for missionary purposes by bilingual Indigenous translators and Rev. John Eliot. The Bible, which was the first to be produced in North America, was first published solely as the New Testament in 1661; a full version followed in 1663. As part of the Corporation for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England, Eliot and others had already translated catechisms, the Gospel of Matthew, Genesis, and Psalms into the Massachusett language in the 1650s. Mamusse wunneetu-panatamwe Up-Biblum God is written in a phoneticized version of Wôpanâak, an Eastern Algonquian language of the Wampanoag homelands which extends through present-day Massachusetts. Rev. Eliot achieved his translations after many years spent learning the language, with the assistance of Native interpreters Cockenoe (Montaukett), John Sassamon (Massachusett), Job Nesuton (Nipmuc), and James Printer (Nipmuc). Versions of this resource have already been digitized by the Internet Archive. The Congregational Library also physically holds a 2nd edition printed in 1680.

BIPOC in Majority-White Church Records

This section is designed to facilitate finding of congregants and clergy of color in majority-white Congregational church and association/consociation records, including those who are solely identified in member rolls, baptisms, marriages, and death records. Various terms were commonly used to identify BIPOC church members or applicants within these records, including “negro,” “mulatto,” “Indian,” “black,” “colored,” “people of colour,” and “col’d.”

In addition to these vital-statistical records, there are also Congregational association records from North Hartford which include several references to Black abolitionist minister Rev. James W. C. Pennington (1807–1870). There is also a rare reference to a slavery transaction within both the church and parish record books of the First Church in York, Maine from the 1730s.

Note: Materials in these records contain outdated and harmful language.

Several Black congregants are identified in the volume Church Records, 1714-1749, in entries dating from 1741-1748.

Barnstable, Mass. East Parish Church

Black and Indigenous members are identified in the volume Church Records, 1725-1816 between 1731 and 1769.

Barnstable, Mass. West Parish Church Records

The records from 1755 mention "Mary Clap an Indian girl."

Bolton, Conn. Congregational Church Records, 1725-1824

Church records include people of African descent.

Boston, Mass. First Church Records, 1690-1825

People of African descent appear in these records between 1652 and the early nineteenth century.

Boston, Mass. Old South Church

Numerous people of African descent were baptized at this church and some were admitted to membership, particularly between 1730 and 1860. Black people are also identified in marriage and death records and in some records of meeting minutes.

Boston, Mass. Second Church Records, 1650-1815

People of African descent appear in these records between 1693 and the late eighteenth century.

Bradford, Haverhill, Mass. First Church of Christ Records, 1682-1915

1731 records note the baptism of Hannah, "an Indian Servant."

Cambridge, Mass. First Church Records, 1638-1783

People of African descent appear in these records between 1698 and 1825.

Canterbury, Conn. Strict Congregational Church Records, 1733-1815

People of Indigenous and African ancestry are noted in these church records between 1729 and 1782.

Cheshire, Conn. First Congregational Church Records, 1717-1813

Membership and death records include people of African descent.

Dorchester, Boston, Mass. First Church Records, 1727-1784

Numerous people of African descent are identified in these records.

Epping, NH Congregational Church Records, 1744-1940

Peter, enslaved by the minister Josiah Stearns, served in the War of Independence and gained his freedom.

Fairfield, Conn. First Church of Christ Records, 1694-1817

Baptism records include people of African descent.

Falmouth, Mass. First Congregational Church

At least five people of African descent are identified in the baptisms and membership rolls of the volume Church Records, 1731-1790, from 1732-1758. A Black couple is identified in the marriage records of 1787.

Franklin, Mass. Congregational Church

Three people of African descent are identified in baptismal records within the volume Church Records, 1737-1781 between 1741-1744.

Grafton, Mass. Congregational Church

Several Black and Indigenous members are identified in baptismal and membership rolls in the volume Church Records, 1731-1774, between 1732 and 1747.

Greenfield Hill, Fairfield, Conn. Greenfield Hill Congregational Church Records, 1668-1878

Baptism records include people of African descent.

Groton, Conn. Church of Christ Records, 1704-1893

Records include free and enslaved people of African descent and Indigenous people.

Guilford, Conn. First Congregational Church Records, 1717-1843

Society ledger contains records of payments to “Moses Negro” for bell ringing and clock repair.

Hampton Falls, NH Congregational Society of Hampton Falls Records, 1712-1754

Records note baptism of “my Indian servant Sippai” by Rev. Theophilus Cotton.

Hanover, Mass. First Congregational Church Records, 1728-1818

Records from 1750 identify three people as "Indians."

Hartford, Conn. First Church of Christ Records, 1684-1910

Membership and death records include people of African descent and Indigenous people.

Hartford North Consociaton Records, 1802-1844

Noted abolitionist and author Rev. James W. C. Pennington was also minister to many churches throughout his life, including Congregational and Presbyterian churches in Connecticut, New York, Mississippi, Maine, and Florida. Having escaped slavery in Maryland at the age of 19, Rev. Pennington went on to attend classes at Yale, receive ordination in the Congregational church, and travel to Europe where he lobbied extensively for the abolitionist cause in America. From 1840-1848 he was minister to the Talcott Street Church (now called Faith Congregational Church) in Hartford, Connecticut. It was during his ministry at Talcott Street that Pennington wrote what is believed to be the first history of African Americans,The Origin and History of the Colored People. Rev. Pennington appears with some regularity in the records of the Hartford North Consociation (those dating after 1840). He is recorded as having led a group of white ministers in prayer on at least one occasion.

Several Black and Indigenous people are identified in the vital records of the church in the mid to late eighteenth century. Adult baptisms and deaths of Black and Indigenous people were noted separately from white congregants by Rev. Ebenezer Gay.

Kingston, NH First Congregational Church Records, 1725-1872

People of African descent are listed in the baptism records.

Lancaster, Mass. First Congregational Church Records, 1708-1846

These records include one or more references to Black or Indigenous people.

Marlborough, Mass. First Church

One congregant was identified as Indigenousin the baptismal records from 1730, in the volume Church Records, 1704-1802. Although the Marlborough First records do not contain other racial notations, additional documentary evidence suggests that at least two people of African descent were baptized between 1763 and 1773.

Mattapoisett, Mass. First Congregational Church

Several Black congregants are identified in the volume Church Records, 1736-1855, from 1742 to 1785.

Merrimac, Mass. Pilgrim Congregational Church

Seven people of African descent (identified as "negro") and one Indigenous member are identified in baptismal records between 1740 and 1772, in the volume Church Records, 1726-1821.

Middleboro, Mass. First Church

This collection contains two lists of church members, which identify five Black and one Indigenous members. Black church members are identified in baptisms and membership rolls between 1735-1754 and between 1773-1796, and in marriage records from at least 1757-1758. See also the relations and disciplinary records associated with Middleboro First members Cuffee/Cuffy Wright, Anna Wright, and Alice/Else Anthony in Firsthand Writings by BIPOC.

Northampton, Mass. First Church of Christ Records, 1661-1845

People of African descent appear in these records between 1735 and 1819.

North Bridgewater, Mass. First Parish Congregational Church

Church members identified as “negro” and “mulatto” are identified in the baptismal, membership, and marriages lists between 1742 and 1781.

Portsmouth, NH Third Congregational Church Records, 1758-1831

These records contain information about a Black woman named Dinah who joined the church in 1791 after experiencing an “awakening” in nearby Kittery, Maine. She was excommunicated in 1796 for allegedly breaking her covenant with the church but was later readmitted to membership in the congregation in 1811.

Rowley, Mass. First Congregational Church Records, 1664-1835

These records include one or more references to Black or Indigenous people.

Salem, Mass. First Church Records, 1629-1843

These records include one or more references to Black or Indigenous people.

Stonington, Conn. First Congregational Church of Stonington Records, 1674-1879

Membership, baptism, and death records include people of African descent and Indigenous people.

Topsfield, Mass. Congregational Church Records, 1684-1869

These records include one or more references to Black or Indigenous people.

Wendell, Mass. Congregational Church

One Black member is identified on the 1782 baptismal list, within the volume Church Records, 1783-1847.

The York records include a rare reference to a slavery transaction enacted by a church committee. In 1732, the committee recorded their decision to procure a slave, identified only as Andrew, for their minister, the Rev. Samuel Moody. The records indicate that Andrew's services were deemed unsatisfactory, and that he was sold on soon and replaced with a hired servant. Although the purchase and ownership of enslaved individuals by Congregational ministers was relatively common practice at this time, its documentation within church and parish records is unusual.

Bedford, Massachusetts. First Church of Christ Records, [1730]-1998. RG 4390. 1 linear foot, 1 microfilm reel.

One person of African descent (identified as "a man of colour") was admitted to membership in 1807.

Boston, Massachusetts. Bowdoin Street Church Records, 1825-1865. RG 0806. 2 linear feet (2 boxes).

Two people of African descent became members of this church between 1828 and 1829. Four people of African descent were interviewed by church leaders between 1828 and 1832, and summaries of these meetings remain in the church records.

Boston, Massachusetts. Green Street Church Records, 1822-1844. RG 1066. 1 volume.

Two Black congregants are identified in the membership lists between 1825 and 1827.

Brewster, Massachusetts. First Congregational Church Records, 1700-1977. RG 1338. 1 microfilm reel.

Several Black people are identified in these records between 1742 and 1750. There is also a discussion about a church member (not ordained) who was disciplined by the church for preaching to Indigenous people.

Hopkinton, New Hampshire. First Congregational Church Clerk Records, 1757-1904. RG 4918. 1 microfilm reel.

A few Black members are identified on the membership, covenant, and baptismal lists between 1767 and 1790.

Medway, Massachusetts. The Community Church Records, 1750-1978. RG 4685. .65 linear feet.

At least three Black people and one Indigenous person are identified in the church records between 1753 and 1785.

Newton, Massachusetts. First Church Records, 1664-1974. RG 0132. 21 linear feet.

One person of African descent (identified as a “Black woman”) is included in the 1797 membership records and three people of African descent are identified in the baptismal records 1797 to 1798.

North Middleboro, Massachusetts. Congregational Church Records, 1747-1927. RG 1381. 1 microfilm reel.

Four Black congregants are identified on the baptismal lists between 1760 and 1766.

In September 1834, when the Second Congregational Church of Woodstock, Connecticut, ordained a new minister, the church included two “colored” women among the one hundred twenty-four church members.

Antislavery and Abolitionist Materials

These resources include the digitized manuscript record books of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, as well as a listing of short-form print materials relating to abolitionist societies which are physically available at the Congregational Library & Archives. These include publications by local and national abolitionist organizations, society minutes and convention proceedings, and copies of lectures and sermons delivered by and for these associations. Some of these records contain references to the “colonization” movement, which sought to relocate both free and emancipated African Americans to West Africa, controversial even at the time for its segregationist ideology. The catalog records for these collections serve as a preliminary starting point for research, but more materials are available in the library collections and, in many cases, are also available online as works in the public domain.

Note: Materials in these records contain outdated and harmful language.

Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society

The Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society (SFASS) was formed in 1834 as an offshoot of the Anti-Slavery Society of Salem and Vicinity (ASSSV). The preamble to the SFASS's constitution stated its three principles: that slavery should be immediately abolished; that African Americans, enslaved or free, have a right to a home in the country without fear of intimidation, and that society should be ready to acknowledge people of color as friends and equals. These principles, in addition to the American Anti-Slavery Society's principles, were in direct opposition to the American Colonization Society, which had been founded in 1817 with the objective to transport emancipated slaves and other free Black people to a perceived "homeland" in West Africa.

Society and Convention Records

Address of the committee appointed by a public meeting, held at Faneuil hall, September 24, 1846, for the purpose of considering the recent case of kidnapping from our soil, and of taking measures to prevent the recurrence of similar outrages: with an appendix. Boston: White & Potter, 1846.

Annual report of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society: with a sketch of the obstacles thrown in the way of emancipation by certain clerical abolitionists and advocates for the subjection of woman in 1837. Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1837.

Church Anti-slavery Society proceedings of the convention which met at Worcester, Mass., March 1, 1859. New York: John F. Trow, 1859.

Constitution and officers of the Essex County Abolition Society, with an address to abolitionists. Salem, MA: William Ives and Co., 1839.

Constitution of the American Convention for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and Improving the Condition of the African Race. Adopted on the 11th day of December 1818, to take effect on the 5th day of October 1819. Philadelphia, PA: Hall & Atkinson, 1819.

Constitution of the Union Congregational Anti-Slavery Society, Providence: formed April 22, 1839. With an address to the beneficent, Richmond-Street and High-Street Congregational Churches. Providence, RI: H.H. Brown, 1839.

Declaration of sentiments and constitution of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, 1861.

Declaration of the National anti-slavery convention / Signed in the Adelphia Hall, in the City of Philadelphia, on the sixth day of December, A.D. 1833. Philadelphia, PA: 1833.

First annual report of the executive committee of the New-Hampshire Congregational and Presbyterian Society for the Abolition of Slavery with the doings of the society at the anniversary meeting held at Francestown, August 24th 1841. Concord, NH: Brown and Colby, 1841.

First annual report of the New-Hampshire Anti-Slavery Society: presented at a meeting of the Society, held at Concord, June 4, 1835. Concord, NH: Elbridge G. Chase, 1835.

Formation of the Massachusetts Abolition Society. Boston: Massachusetts Abolition Society, 1839.

Minutes and proceedings of the second annual Convention, for the Improvement of the Free People of Color in these United States: held by adjournments in the city of Philadelphia, from the 4th to the 13th of June inclusive, 1832. Philadelphia, PA: Martin & Boden, 1832.

Proceedings of the American Anti-slavery Society at its second decade, held in the city of Philadelphia, Dec. 3d, 4th and 5th, 1853. Westport, CT: Negro Universities Press, 1854.

Proceedings of the American Anti-slavery Society at its third decade, held in the city of Philadelphia, Dec. 3d, 4th, 1864. New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1854.

Proceedings of the Anti-slavery Convention of American Women, held in Philadelphia. May 15th, 16th, 17th and 18th, 1838. Philadelphia, PA: Merrihew and Gunn, 1838.

Proceedings of the Anti-slavery convention of American women, held in Philadelphia. May 1st, 2d and 3d, 1839. Philadelphia, PA: Merrihew and Thompson, 1839.

Proceedings of the Convention of Ministers of Worcester County, on the subject of slavery: held at Worcester, December 5 & 6, 1837, and January 16, 1838. Worcester, MA: Massachusetts Spy Office, 1838.

Proceedings of the New England Anti-Slavery Convention, held in Boston on the 27th, 28th and 29th of May, 1834. Boston: Garrison & Knapp, 1834.

Proceedings of the Norfolk County Anti-slavery Convention held at Dedham, January 26, 1838. Quincy, MA: J.A. Green, 1838.

Proceedings of the Pennsylvania convention, assembled to organize a state anti-slavery society, at Harrisburg, on the 31st of January and 1st, 2d and 3d of February 1837. Philadelphia, PA: Merrihew and Gunn, 1837.

The Boston mob of 'gentlemen of property and standing.': Proceedings of the anti-slavery meeting held in Stacy Hall, Boston, on the twentieth anniversary of the mob of October 21, 1835. Phonographic report by J.M.W. Yerrinton. Boston: R.F. Wallcut, 1855.

The declaration and pledge against slavery: adopted by the Religious Anti-Slavery Convention held at the Marlboro' Chapel, Boston, February 26, 1846. Boston: Devereux & Seaman, 1846.

The report and proceedings of the first annual meeting of the Providence Anti-slavery Society: with a brief exposition of the principles and purposes of the abolitionists. Providence, RI: H.H. Brown, 1833.

Lectures and Sermons

Ballou, Adin. A discourse on the subject of American slavery: Delivered in the First Congregational meeting house, in Mendon, Mass., July 4, 1837. Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1837.

Buchanan, George. An oration upon the moral and political evil of slavery. Delivered at a public meeting of the Maryland society, for promoting the abolition of slavery, and the relief of free negroes, and others unlawfully held in bondage. Baltimore, July 4th, 1791. Baltimore: Philip Edwards, 1793.

Burt, J. The law of Christian rebuke: A plea for slave-holders: A sermon, delivered at Middletown, Conn., before the Anti-slavery Convention of Ministers and Other Christians, October 18, 1843. Hartford: N.W. Goodrich and Co., 1843.

Cheever, George B. The fire and hammer of God's word against the sin of slavery / Speech of George B. Cheever at the anniversary of the American Abolitionist Society, May 1858. New York: American Abolition Society, 1858.

Child, David Lee. The despotism of freedom, or, The tyranny and cruelty of American republican slave-masters: Shown to be the worst in the world: In a speech, delivered at the first anniversary of the New England Anti-Slavery Society. Boston: Boston Young Men's Anti-Slavery Association, 1833.

Claggett, William. An address, delivered before the Portsmouth anti-slavery society on the fourth of July, A.D. 1839, being the 63d anniversary of the independence of the United States of America. Portsmouth, NH: C. W. Brewster, 1839.

Clarke, Walter. The American Anti-Slavery Society at war with the church: A discourse, delivered before the First Congregational Church and Society, in Canterbury, Conn., June 30th, 1844. Hartford: Elihu Geer, 1844.

Douglass, Frederick. The anti-slavery movement a lecture / by Frederick Douglass, before the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. Rochester, NY: Lee, Mann & Co., 1855.

Douglass, Frederick. Two speeches / by Frederick Douglass; one on West India Emancipation, delivered at Canandaigua, Aug. 4th, and the other on the Dred Scott Decision, delivered in New York, on the occasion of the anniversary of the American Abolition Society, May, 1857. Rochester, NY: C.P. Dewey, 1857.

Garrison, William Lloyd. An address, delivered before the Old Colony Anti-slavery Society, at South Scituate, Mass., July 4, 1839. Boston: Dow & Jackson, 1839.

Garrison, William Lloyd. An address on the progress of the abolition cause delivered before the African Abolition Freehold Society of Boston, July 16, 1832. Boston: Garrison and Knapp, 1832.

Granger, Arthur. The Apostle Paul's Opinion Of Slavery And Emancipation.: A Sermon Preached To The Congregational Church And Society In Meriden, At the request of several respectable Anti-Abolitionists. Middletown: Charles H. Pelton, 1837.

Grosvenor, Cyrus Pitt. Address before the Anti-Slavery Society of Salem and the vicinity: In the South Meeting-House, in Salem, February 24, 1834. Salem, MA: Ives Observer Press, 1834.

Harris, Thaddeus Mason. A discourse delivered before the African Society in Boston, 15th of July, 1822, on the anniversary celebration of the abolition of the slave trade. Boston: Phelps and Farnham, 1822.

Kellogg, Giles B. An oration delivered July 4, 1829, before the Anti-Slavery Society of Williams College. Williamstown, MA: Ridley Bannister, 1829.

Latrobe, John H. B. Colonization and abolition. An address delivered by John H.B. Latrobe, of Maryland, at the anniversary meeting of the New York state colonization society, held in Metropolitan hall, May 13th, 1852. Baltimore: John D. Toy, 1852.

Morse, Jedidiah. A discourse, delivered at the African meeting-house, in Boston, July 14, 1808, in grateful celebration of the abolition of the African slave-trade, by the governments of the United States, Great Britain and Denmark. Boston: Lincoln & Edmands, 1808.

Rogers, Nathaniel P. An address delivered before the Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society: At its annual meeting, 25 Dec. 1837. / by Nathaniel P. Rogers; to which is added, the third annual report of said society. Concord, NH: W. White, 1838.

Root, David. The abolition cause eventually triumphant : a sermon, delivered before the Anti-slavery society of Haverhill, Mass., Aug. 1836. Andover: Gould and Newman, 1836.

Ruffner, William Henry. Africa's redemption. A discourse on African colonization in its missionary aspects, and in its relation to slavery and abolition. Preached on Sabbath morning, July 4th, 1852, in the Seventh Presbyterian church, Penn square, Philadelphia. Philadelphia, PA: W.S. Martien, 1852.

Sumner, Charles. The anti-slavery enterprise: Its necessity, practicability, and dignity, with glimpses at the special duties of the North: An address before the people of New York at the Metropolitan Theatre, May 9, 1855. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1855.

Thome, James A. and Cox, Samuel H. Debate at the Lane Seminary, Cincinnati. Speech of James A. Thome, of Kentucky, delivered at the annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society, May 6, 1834. Letter of the Rev. Dr. Samuel H. Cox, against the American Colonization Society. Boston: Garrison & Knapp, 1834.

Thompson, George and Breckinridge, Robert J. Discussion on American slavery, between George Thompson, agent of the British and Foreign Society for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the world, and Robert J. Breckinridge, delegate from the General assembly of the Presbyterian church in the United States to the Congregational union of England and Wales: holden in the Rev. Dr. Wardlaw's chapel, Glasgow, Scotland, on the evenings of the 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th of June, 1836. Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1836.

Williams, Peter. An oration on the abolition of the slave trade; delivered in the African church, in the city of New York, January 1, 1808. New York: S. Wood, 1808.

Pamphlets and Tracts

Address of the Free Soil Association of the District of Columbia to the people of the United States: Together with a memorial to Congress, of 1060 inhabitants of the District of Columbia, praying for the gradual abolition of slavery. Washington: Buell & Blanchard, 1849.

An address to the free people of colour and descendants of the African race, in the United States / by the American Convention for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and Improving the Condition of the African Race. Philadelphia, PA: Hall & Atkinson, 1819.

A vindication of female anti-slavery associations. London: Female Anti-Slavery Society, n.d.

An appeal to the women of the nominally free states, issued by Anti-slavery Convention of American Women, held by adjournments from the 9th to the 12th of May, 1837. Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838.

Address of the Congregational Union in Scotland to their fellow Christians in the United States on the subject of American slavery. New York: American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, 1840.

Address of the New York City Anti-Slavery Society to the people of the city of New York. New York: West & Trow, 1833.

Address to the churches of Jesus Christ, by the Evangelical Union Anti-slavery Society, of the city of New York, auxiliary to the Am. A.S. Society; with the constitution, names of officers, board of managers, and executive committee. April, 1839. New York: S.W. Benedict, 1839.

Bacon, Leonard. Review of pamphlets on slavery and colonization. New-Haven: A.H. Maltby; 1833.

Bassett, William. Letter to a member of the Society of Friends, in reply to objections against joining anti-slavery societies. Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1837.

Boston Female Anti-slavery Society. Right and wrong in the anti-slavery societies. Boston: W.S. Dorr, 1840.

Colonization and abolition considered: Or, some remarks on the sixteenth annual report of the American Colonization Society. Springfield, Ill: Lincoln Bindery Co., ca. 1833.

Fee, John G. An anti-slavery manual: Or, The wrongs of American slavery exposed by the light of the Bible and of facts, with a remedy for the evil. New York: W. Harned, 1851.

Follen, Eliza Lee Cabot. Anti-slavery hymns and songs. New York: 1855.

Garrison, William Lloyd. The 'infidelity' of abolitionism. New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1860.

Goodell, William. One more appeal: To professors of religion, ministers, and churches, who are not enlisted in the struggle against slavery. Boston: New England Anti-Slavery Tract Association, 1843.

Higginson, T.W. Does slavery Christianize the negro? New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1855.

Hildreth, Richard. What can I do for the abolition of slavery? Boston: New England Anti-Slavery Tract Association, ca.1840.

Hugo, Victor et al. Letters on American slavery from Victor Hugo, de Tocqueville, Emile de Girardin, Carnot, Passy, Mazzini, Humboldt, O. Lafayette--etc. Boston: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1860.

Kelley, William D. et al. The equality of all men before the law claimed and defended / in speeches by Hon. William D. Kelley, Wendell Phillips, and Frederick Douglass, and letters from Elizur Wright and Wm. Heighton. Boston: Rand & Avery, 1865.

Stewart, Alvan. The creed of the Liberty Party abolitionists: Or, their position defined, in the summer of 1844, as understood. Utica: Jackson & Chaplin, 1844.

The constitutional duty of the federal government to abolish American slavery: An exposé of the position of the Abolition society of New-York city and vicinity. New York: Abolition Society of New-York City, 1855.

Thurston, David. An Address to the anti-slavery Christians of the United States. New York: J.A. Gray, 1852.

Webster, J. C. and Cheever, Henry T. Circular [declaration of principles and constitution of the Church Anti-Slavery Society of the United States]. Worcester: 1858.

Whipple, Charles E. Relations of anti-slavery to religion. New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1856.

Further Reading

The following bibliography includes three sections: (1) links to online articles, (2) catalog links to published materials physically available at the Congregational Library, and (3) other volumes available elsewhere. These resources are intended to provide additional context for each of the sections in this research guide.

Boles, Richard J. "Documents Relating to African American Experiences of White Congregational Churches in Massachusetts, 1773-1832." The New England Quarterly 86, no. 2 (June 2013): 310-323.

Cameron, Christopher. "The Puritan Origins of Black Abolitionism in Massachusetts." Historical Journal of Massachusetts 39, no. 1-2 (2011): 78-107.

Cooper, James F. "Cuffee’s ‘Relation’: A Faithful Slave Speaks Through the Project for the Preservation of Congregational Church Records." The New England Quarterly 86, no. 2 (June 2013): 293-310.

Minkema, Kenneth P., and Stout, Harry S. “The Edwardsean Tradition and the Antislavery Debate, 1740–1865.” Journal of American History 92, no. 1 (June 2005): 47–74.

Seeman, Erik R. "'Justise Must Take Plase': Three African Americans Speak of Religion in Eighteenth-Century New England." The William and Mary Quarterly 56, no. 2 (April 1999): 393-414.

Sherer, Robert Glenn Jr. "Negro Churches in Rhode Island Before 1860." Rhode Island History 25, no. 1 (January 1966): 9-24.

Simmons, William S. "Red Yankees: Narragansett Conversion in the Great Awakening." American Ethnologist 10, no. 2 (May 1983): 253-271.

Whiting, Gloria McCahon. “Power, Patriarchy, and Provision: African Families Negotiate Gender and Slavery in New England.” Journal of American History 103, no. 3 (December 2016): 583–605.

Aghahowa, Brenda Eatman. Praising in Black and White: Unity and Diversity in Christian Worship. Cleveland, OH: United Church Press, 1996.

American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. Shall We Give Bibles to Three Millions of American Slaves? New York: American and Foreign Anti-slavery Society, 1847.

American Convention for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and Improving the Condition of the African Race. An address to the free people of colour and descendants of the African race, in the United States. Philadelphia, PA: Hall & Atkinson, 1819.

American Missionary Association. Annual Reports, 1847-1936. Bound Reports, 15 Volumes.

Anderson, Emma. The Betrayal of Faith: The Tragic Journey of a Colonial Native Convert. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Andrews, Edward E. Native Apostles: Black and Indian Missionaries in the British Atlantic World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013.

Apess, William. On our Own Ground: The Complete Writings of William Apess, a Pequot. Ed. Barry O'Connell. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992.

Bailey, Richard A. Race and Redemption in Puritan New England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Boles, Richard J. Dividing the Faith: The Rise of Segregated Churches in the Early American North. New York: New York University Press, 2020.

Brekus, Catherine. Sarah Osborn’s World: The Rise of Evangelical Christianity in Early America New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013.

Bross, Kristina. Dry Bones and Indian Sermons: Praying Indians in Colonial America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004.

Butler, Jon. New World Faiths: Religion in Colonial America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Cogley, Richard W. John Eliot’s Mission to the Indians before King Philip’s War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Conforti, Joseph A. Saints and Strangers: New England in British North America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Culver, Dwight W. Negro Segregation in the Methodist Church. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1953.

Cummins, George D. The African a trust from God to the American: A sermon delivered on the day of national humiliation, fasting and prayer, in St. Peter's Church, Baltimore, January 4, 1861. Baltimore, MD: J.D. Toy, 1861.

Eddy, Ansel Doane. "Black Jacob," a monument of grace.: The life of Jacob Hodges, an African negro, who died in Canandaigua, N. Y., February 1842. Philadelphia, PA: American Sunday-School Union, 1842.

Fisher, Linford D. The Indian Great Awakening: Religion and the Shaping of Native Cultures in Early America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Goddard, Ives, and Bragdon, Kathleen. "Native Writings in Massachusett." Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society, 1988.

Greene, Lorenzo Johnston. The Negro in Colonial New England. New York: Athenaeum, 1969.

Hamilton, Charles V. The Black Preacher in America. New York: William Morrow, 1972.

Haynes, Leonard L. The Negro Community Within American Protestantism, 1619-1844. Boston: Christopher Publishing House, c. 1953.

Hopkins, Samuel. Timely Articles on Slavery. Boston: Congregational Board of Publication, 1854.

Horton, James Oliver and Horton, Lois E. In Hope of Liberty: Culture, Community and Protest among Northern Free Blacks, 1700–1860. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Logan, Samuel Crothers. Correspondence Between the Rev. S.C. Logan, Pittsburgh, Pa., and the Rev. Dr. J. Leighton Wilson, Columbia, S.C. Columbia, SC: Office of the Southern Presbyterian, 1868.

Mandell, Daniel R. Tribe, Race, History: Native Americans in Southern New England, 1780–1880. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011.

Manegold, C.S. Ten Hills Farm: The Forgotten History of Slavery in the North. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Morrison-Reed, Mark D. Black Pioneers in a White Denomination. Boston: Beacon Press, c. 1984.

Murray, Andrew E. Presbyterians and the Negro: A History. Philadelphia, PA: Presbyterian Historical Society, 1966.

Newcomb, Harvey. "The 'Negro Pew": Being an Inquiry Concerning the Propriety of Distinctions in the House of God, on Account of Color. Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1837.

Newman, Richard. "Lemuel Haynes on Baptism: An Unpublished Manuscript from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture." Bulletin of Research in the Humanities 87, no. 4 (1986-1987): 509-514.

O'Brien, Jean M. Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Piersen, William Dillon. Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988.

Saillant, John. Black Puritan, Black Republican: The Life and Thought of Lemuel Haynes, 1753-1833. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Scherer, Lester B. Slavery and the Churches in Early America, 1619-1819. Grand Rapids, IA: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1975.

Silverman, David J. Faith and Boundaries: Colonists, Christianity, and Community among the Wampanoag Indians. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Silverman, David J. Red Brethren: The Brothertown and Stockbridge Indians and the Problem of Race in Early America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010.

Stanley, Alfred Knighton. The Children is Crying: Congregationalism Among Black People. New York: Pilgrim Press, 1979.

Stanley, J. Taylor. A History of Black Congregational Christian Churches of the South. New York: United Church Press for the American Missionary Association, c. 1978.

Warren, Wendy. New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America. New York: W.W. Norton, 2016.

Williams, Ethel L. Biographical Directory of Negro Ministers. New York: Scarecrow Press, 1965.

Winiarski, Douglas L. Darkness Falls on the Land of Light: Experiencing Religious Awakenings in Eighteenth-Century New England. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Adams, Catherine, and Pleck, Elizabeth. Love of Freedom: Black Women in Colonial and Revolutionary New England New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Berlin, Ira. Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1998.

Blee, Lisa and O'Brien, Jean M. Monumental Mobility: The Memory Work of Massasoit. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Breen, Louise A. Daniel Gookin, The Praying Indians, and King Philip’s War. New York: Routledge Publishers, 2019.

Brooks, Lisa. Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018.

Cameron, Christopher. To Plead Our Own Cause: African Americans in Massachusetts and the Making of the Antislavery Movement. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2014.

Clark-Pujara, Christy. Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island. New York: New York University Press, 2016.

Conforti, Joseph. “Samuel Hopkins and the Revolutionary Antislavery Movement.” Rhode Island History 38, no. 2 (May 1979).

DeLucia, Christine M. Memory Lands: King Philip’s War and the Place of Violence in the Northeast. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018.

Fitts, Robert K. Inventing New England’s Slave Paradise: Master/Slave Relations in Eighteenth Century Narragansett, Rhode Island. New York: Taylor and Francis, 1998.

Gerbner, Katherine. Christian Slavery: Conversion and Race in the Protestant Atlantic World. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

Hardesty, Jared R. Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019.

Hardesty, Jared R. Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston. New York: New York University Press, 2016.

Hinks, Peter. "Timothy Dwight, Congregationalism, and Early Antislavery." The Problem of Evil: Slavery, Freedom, and the Ambiguities of American Reform (2007): 148-61.

Johnson, Joseph. To Do Good to My Indian Brethren: The Writings of Joseph Johnson, 1751-1776. Ed. Laura J. Murray. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998.

Kopelson, Heather Miyano. Faithful Bodies: Performing Religion and Race in the Puritan Atlantic. New York: NYU Press, 2014.

Mandell, Daniel R. Behind the Frontier: Indians in Eighteenth-Century Eastern Massachusetts Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

Melish, Joanne Pope. Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780–1860. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998.

Newell, Margaret Ellen. Brethren By Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015.

O’Brien, Jean M. Dispossession by Degrees: Indian Land and Identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650–1790. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Occom, Samson. The Collected Writings of Samson Occom, Mohegan. Ed. Joanna Brooks. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Price, H. H. and Talbot, Gerald E. Maine's Visible Black History: The First Chronicle of Its People. Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House Publishers, 2006.

Romer, Robert H. Slavery in the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts. Florence, MA: Levellers Press, 2009.

Romero, Todd R. Making War and Minting Christians: Masculinity, Religion, and Colonialism in Early New England. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011.

Rubin, Julius H. Tears of Repentance: Christian Indian Identity and Community in Colonial Southern New England. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2013.

Silverman, David. This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.

Sweet, John Wood. Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730–1830. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

Tisby, Jemar. The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism. Grand Rapids, IA: Zondervan, 2019.

Towner, Lawrence W. A Good Master Well Served: Masters and Servants in Colonial Massachusetts, 1620–1750. New York: Garland Publishing, 1998.

Warren, James A. God, War and Providence: The Epic Struggle of Roger Williams and the Narragansett Indians Against the Puritans of New England. New York: Scribner, 2018.